For My Father, By Emine Ceylan

He was born in 1922. It was in the month of April but the exact date of birth is unknown. He was born in Çakıroba village in Çanakkale’s Yenice township. His father, Koca Nuri, had fought in the first world war for quite some time and was thought to have been killed–until one day years later he suddenly showed up again. His mother, Fatma, was a handsome woman whose previous young husband had been killed in the same war. He was the eldest of three brothers. These three boys, each one utterly different from the other two and with only a year or two of age separating them, grew up in the midst of an poor family in the rolling countryside of Çakıroba. While not quite on the scale of the Brothers Karamazov, the Brothers Ceylan never lacked for disputes, conflicts, and contradictions in the course of their lives. Nor did their father for that matter. Like the patriarch Karamazov, their father too was a huge, extremely handsome man who was fond of worldly delights: a hedonistic, exuberant, sociable, blue-eyed man who was not too fond of work.

Of the three brothers, he was the only one with an education. Of the other two, one lived out his life in the village in which he was born while the other chose to go off and lose himself in the turmoil of the big city. He completed primary school in Yenice, walking all the way there from the village and back every day. His education continued with middle school in Biga and with lycee in Balıkesir. A basement room was rented in town for him to stay in: a tiny room with bare white walls and a single bare light bulb hanging down from the ceiling. In the middle of the room was a suitcase that did service as a table of sorts and along one wall was a bed. In addition to his own penury, there was a war going on at the time and bread was being rationed. Still hungry after finishing what he’d been given for lunch, he’d often eat the evening allotment as well, which meant going hungry for the rest of the day and night.

Want… Poverty… Loneliness… In a setting in which everything and everyone was dragging him down, he found respite perhaps in the footpaths that led down into the ravines below the village on the hill, in flowers that blossomed of a morning, in plashing streams, and also perhaps in trees, with which he was in love even in those early days. This was a love of nature which most certainly was shaped at that time and which elevated him above everything else. Thoughts that went unexpressed and formed the background of life sprouted amidst such misty landscapes.

A youth who was tutored by poverty; who was determined to keep moving forward, without letup and alone; a youth who rejected religious conditioning and superstition…

A youth who put the summit of loneliness to the test and consecrated himself to it… A youth who was utterly committed to reaching the end of any path on which he embarked, who advanced along it just as he saw fit and without paying attention to society’s judgments or suspicions.

A youth who was not daunted by suffering and who had not yet lost the things that he loved: Mehmet Emin Ceylan…

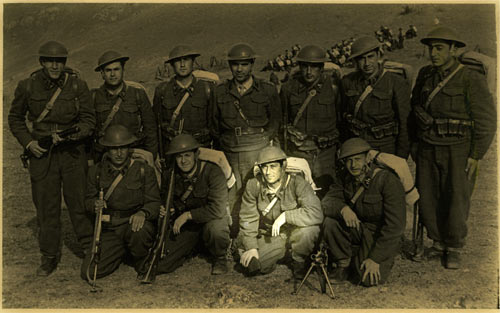

Military Service, 1950 |

In summers he returned to the village and threw himself into work: cultivating and harvesting tobacco. On evenings overflowing with stars he’d stretch himself out and lose himself in reverie where he lay. The distant sound of dogs barking, the sudden day’s final call to prayer... Followed by the return of a silence in which the world grew remote, distances protracted, and he dropped off into sleep. He’d forget that he was supposed to be keeping watch on the cornfield, that the reason he was there was to drive off the boars that visited the fields at night. He’d be reminded though by the sound of boars munching on corn and stirred into action he’d race off in the direction the noise was coming from and the frightened boars would quickly run away.

After graduating from lycee he wanted to enroll in the agricultural faculty. He went to İstanbul and that was the only entrance exam he sat for. He passed and began studying at the agricultural university in Ankara. This was the first time in his life that he put on an overcoat: part of his allotment of the assistance that the government gave to poor students was a black overcoat. He was a taciturn young man, one not much given to talk. He never took much part in his friends’ boisterousness, choosing instead to advance towards his dreams. He never had much of a chance to wear the overcoat that the government had given him either: he sold it and used the money to buy a language course on phonograph records. Through continuous hard work he learned pretty good English.

“Those who love truth must seek love–which is to say love that is not an illusion–in marriage” Camus once said.

And he took his own step in that direction.

“My beloved fiancée,

Although I wish I could write to you more often I never seem to manage to. My most joyful days and moments are the ones when I’ve had word from you. I never could forget you. Your memory is always with me in the throne of my heart. No matter how much difficulty I may be in, just the memory of you is enough to make everything better and to dispel all my sadness. I am overcome with joy thinking about the home that you and I will have one day in the future…”

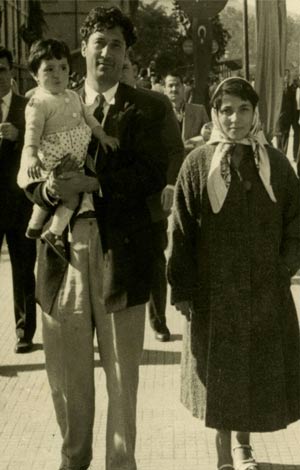

Marriage, 1952 |

They were married in 1952. Her name was Fatma Bodur and she was from Nevruz. They settled down in Bursa, where he had first been employed after his military service.

In 1954 he successfully passed an English proficiency exam held by the government and went to the United States, leaving behind a young wife and an as yet unborn child.

The year that he spent in America opened up a brand new period in his life. He was much impressed by the country’s level of development and by its liberty. Scrimping and saving up his government allowance he used the money to buy a 1957 model Chevrolet and some household goods. He traveled around different parts of the country, visiting universities, learning first-hand about developments in agriculture, and even giving lectures about Turkey.

First years of the Marriage, 1954 |

“Our son,

Fatma has given birth to a girl at the Gureba hospital. She’s safe and sound and the baby’s health is quite good. She want to name the baby after her mother, Emine Müberra. May this be auspicious and beneficial for us all May God grant the baby and you all long lives.

Your Father, 8 January 1955”

“…How’s the girl? Is she beautiful? Of course I shouldn’t have to ask that because she must take after you. Best wishes for a long and prosperous life…"

"…Darling, my first objective is to bring back a car that can be sold for twenty-five thousand liras and, if I have enough money left, a big refrigerator. (I won’t be selling that.) Next an electric washing machine and then an electric stove. But first of all a car and if I don’t have enough money and can’t buy you something you won’t be cross now, will you? I’ve bought a four-dollar camera for now. On the way back I’ll get a better one in Italy or Switzerland…”

“… Darling as you know I spent a month and a half on a ranch in Utah. During that time I worked very hard and it was exhausting. I got up at 5 in the morning every day and didn’t get back home until 6 in the evening. I was afoot for 13 hours every day. Just so they wouldn’t charge me anything…”

“…I’m so sorry that I still haven't’ been able to get a camera. So many precious memories are just disappearing but there’s nothing to be done about it. I console myself by remembering the difficult times in Turkey and saying that it wouldn’t be right to pay money for pictures. I mean even if I suppose that I’ll be able to sell the car for 25-30 thousand liras there, that will only increase by a little in the next ten years but by that time I’ll be over 40. What good will the money be then? Like I said before, I’ve spent my whole life so far saving up money. The time has come now for me to come to my senses and stop drifting along like a log caught in a torrent. The reason I’m telling you all this is my wish to have your ideas and advice. …”

“… “What good will the money be then?” you say. I’ve heard many people say that a man’s life begins after 40. But so what if we haven’t got money? It’ll be enough if our lives are happy. We earn enough to get by…”

“…Why lie about it? I’m doing without entertainment, clothes, a little bit of just about everything. I’ll have to put up with it. That’s the way my life has always been. But I’m fed up with it. Let this be the last time.…”

But it wasn’t the “last time”. That’s the way his life always would be. He did bring back a car–but was unable to clear it through customs. He spent no less than five years in the effort. He launched a legal battle to get that car out. He memorized all the laws and fought with enormous strength. In the end, he got the car. That was followed by a suit against the government for damages–which he won and for which he was paid ten thousand liras.

That car’s still in the garage–inconceivable that it should ever be sold or given away. That automobile said so many things to him because of the role it had played in his inability to realize so many of the things he had planned in the springtime of his life. It accompanied its avid owner and together they grew old, first in Yenice for a while then in a rural garage and finally in a garage in İstanbul. My father would spend a part of his time every day in the garage. No one knows what he did there, what he looked after, what he thought, or what he felt.

Days of the city of Bursa, 1956 |

On returning from America he began working at the Agricultural Research Institute in Yeşilköy. A son was born to him on the 26th of January in 1959. He wanted to give the baby a “historical” name–something like Gültekin, Bilge, or Kağan –and opted for “Bilge”. With the addition of my grandfather’s name, his son became “Nuri Bilge”.

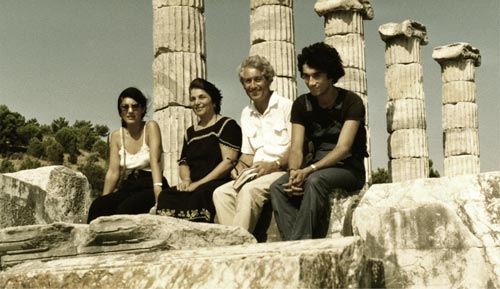

We always think of our father in a variety of contexts: the obligatory afternoon naps we were made to take and the fish oil we had to drink when we were kids; his poring over maps at night and his dreams of traveling to New Zealand on official duty–dreams which for whatever reason never materialized; the long periods of taciturnity at night that he spent among his books; his brooding withdrawals into his own world; the trips we used to take in that precious automobile of his–there must not be a single ancient site in Turkey that we didn’t eventually go and see. We recall visits to the Beyazıt library: Miletos, Priene, Ephesos, Termessos, Sardis, and so on and so on. My father was familiar with even the remotest places. He read books in English and French too. He idolized Alexander the Great :

“... Someone who doesn’t know the past can’t know the future either. I wanted to understand the mystery of someone who managed to make it all the way from Macedonia to Egypt and India. That’s no small thing. The last place he reached was the Hyphasis, the last river in the Punjab. It’s called the Beas today. He died while preparing for his Arabian campaign. First and foremost he was an accomplished man. He was a pupil of Aristotle after all. “My father gave me life” he used to say “and Aristotle taught me how to use it.” He wasn’t the only one–there were others whom I admired of course. For example Urukagina, a virtuous man who was both the instructor and the servant of the people of Mesopotamia. Urukagina was a king of Lagash and emerged at a time when the priestly class was exploiting the people….”

(Kış Yolculuğu, “Mısır Tarlası”, p 33.)

When we visited ancient sites my mother, my brother, and I would usually sit in the shade of a tree somewhere near the entrance while my father would disappear behind a hill carrying a couple of books. An hour or two later his silhouette might appear atop some other hill and then disappear again. There was always a light in his eyes and a happy smile on his lips. At the time of course we couldn’t understand how such a passionate person as he could do all of these things by himself, how many things there were in his life that he really never imparted to anyone else, or how such solitary happiness as this was sufficed to him all his life. Hours later he would suddenly reemerge, tired but happy, and we’d all continue on our way. We used to wonder why father was so interested in these things. Whenever he told us about them, we’d listen with stupefied astonishment and curiosity.

His messages would always be “Now that’s the meaning of life” and “No matter how transitory they many be, our lives will find a place of their own within the magnificence of history” and “Science, art, and knowledge are all and everything else is vain.”

Open air cafe, Bursa, 1958 |

It was many years later when my father and I went to Alexandria that I realized it. As we wandered through streets in the midst of old houses that were dominated by a dingy sepia color there in that beautiful old city or walked along the waterfront stretching before the city with the hot sea breezes licking our faces of an evening, I understood that my father wasn’t really here in the present. His attention was not attracted by groups of high-spirited people nor did he show any interest in a man whose animated face assumed a host of different expressions. He uttered not a word about the worn-out, tattered, and melancholy demeanor of this city that seemed to crush the people that dwelt in it now and yet invited them to partake in tranquility. It was as if he himself was living in some fragment of ancient time and what we saw was just his facsimile. I always admired his ability to devote himself so utterly, when thinking about something, when looking at a rock.

In front of the house in Bakırköy, İstanbul, 1958 |

In 1962 we moved to Yenice. He wanted to do something for his hometown. He wanted to put the things he’d learn to work there. He experienced disappointments during the many years that he spent there but he was nevertheless happy. Perhaps due to his nature he was never much in harmony with society and he withdrew quite thoroughly into solitude. On the extensive property he inherited from his father he farmed, taught French, did agricultural engineering, and so on.

“…I also believe in Nature, in its infinity. Concealed within even a tiny sapling that we look briefly at and pass by is a marvel of nature. For example every year it puts out a new branch and if the branch is short, that means there was not much rain that year. Nature contains within itself the answer to every question that may be in our minds. A person should feel himself as a part of this whole. He should accept that he is a cog on its magnificent wheel and be content about it…

(Kış Yolculuğu, “Mısır Tarlası”, p 40.)”

We’re standing in a field stretching down the slope as far as the eye can see. The sun is overhead. It’s the hottest part of the afternoon. Bilge and I want to go swimming at Kemer by the Marmara sea over the weekend. Even the dream of that was enough to make us happy. Father had promised to take us there if we did our work well. A machine was operating incessantly in the shade of the trees. Tomatoes were being gathered and emptied into it to make paste. The paste was emptied into tins. With the burning sun over our heads we gathered tiny tomatoes in baskets. The tomatoes’ leaves made our hands itch. Once in a while I’d look out and see the sea and its waves down below. With one last effort my hands reach for the tomatoes scattered on the ground. Immersed in his work as always, Father was bustling about, now under the trees, now in the middle of the field. He was tired, but also quite happy. As for my brother and I, we endured it all with the strength of our dream of going to the seaside… We didn’t go to the seaside that weekend. Or the next one either.

Whenever I catch the scent of a tiny tomato on a hot summer day or grasp one in my hand, those days suddenly flood forth from the depths of my memory together with the smell and image of an azure sea and its waves.

With his son, Istanbul, 1959 |

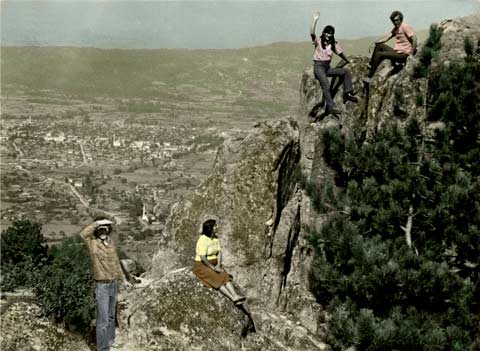

Early in the 70s my mother, brother, and I came to İstanbul for our education. We bid farewell to small-town life, which had played an important role in the development of our personalities, and to its meadows and ancient cemeteries, to the huge “Issız Cuma” plane tree that inspired both terror and curiosity in us, to childhood games, to the pear trees that we raced around under, to the dark nights that enriched our dreams, to the long and snowy winters; even to “Devil’s Rock”, which was located on Mt Asar jutting out right at the edge of town and to which we climbed with great difficulty once or twice a year.

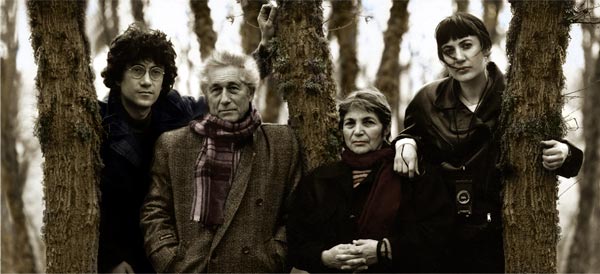

Portrait of the Family, Yenice, Çanakkale, 1965 |

Unable to arrange a transfer, Father stayed behind. Many years passed and there, alone in the midst of nature, he erected a life for himself. Every day he’d leave his house in Yenice and go by bike to the field. He no longer raised anything on it though: he very much loved its wild, weed-covered condition as well. All of the past experiments (apples, wheat, tomatoes, etc) were now things of the past. He made his way among the poplar trees that demarcated the field. He took care of the day-to-day business, digging open a new irrigation channel, cutting wood, keeping himself busy with a thousand and one chores that he created for himself. When he was tired he’d stretch out in his hammock and drowse off watching the gently swaying upper branches of oak trees reaching into the sky, trees that he had raised himself, trees whose growth he had been witness to day after day. Towards evening he’d leave the house, shutting behind him the wooden door that he’d fashioned himself. Sometimes he’d head up the path covered by pine needles that led to the old village cemetery and spend some times by the graves there in which his mother, father, brother, and other relatives were buried. He recalled their memories not with prayer but as beings that had joined infinity and each become one with the rustlings of pine trees ascending into the sky, with Nature. He remembered them not with grief but with reverence. After that he’d head off along the path towards the village, pass by the coffin plinth standing there in the midst of exquisitely-formed rocks that seemed to have been carved by a master sculptor, and reach the house where he’d spent his childhood and in which no one lived any more. Sometimes he’d go into the yard and his eye would be caught by new mulberry tree shoots. Next his gaze would shift to the well way down below. Suddenly it would be as if this house, in which the members of the Ceylan family who had now joined infinity and who once had exuberantly lived out lives in poverty, were shorn of all its present reality. Colorful flowers bloomed around the stone steps. With a smile on his lips, he’d open the wooden door and go out. Mounting his bicycle, he’d make the return trip. Villagers working their fields in the last rays of daylight would take a habitual look at the figure of an old man racing by on a bicycle in the distance and return to their business.

The nights too were always the same. Surrounded by a multilingual pile of books he’d nod off remote from and unconcerned with the changing order of the world, or fashion, or anything that most other people would call life…

Devil's Rock, Yenice, Çanakkale, 1978 |

Years later my brother Bilge turned to cinema and after the short film Koza, in which he had our parents play roles, and Kasaba, an account of our own childhoods, he shot Mayıs Sıkıntısı (Clouds of May), the focal point of which he made Father. This was quite an entirely different experience for Father but he found it not very difficult to act in this movie consisting of excerpts from his own life. The father who had been rendered immortal by Bilge’s film was no longer just “our” father but the inimitable actor of Mayıs Sıkıntısı and Kasaba. He cherished a letter that he’d received from a fan in Brazil and also saved everything written about the films as well. All the awards were proudly arrayed on top of the house’s sideboard. He was proud of his son–and of himself as well. Mayıs Sıkıntısı won him the “best actor” prize at the Alexandria Film Festival in 2000.

These movies gleamed like stars not just in the history of cinema but in his personal history as well. And they will continue to shine.

As for my brother and I, well we’re overflowing with recollections of the struggles to which he dedicated his life: the struggles he waged against the uneducated, conditioned townsfolk, the prolonged court suits he initiated to protect trees, the building that he and my mother incredibly had built against all the odds, the automobile suit, and so on.

Priene Ruins, 1983 |

Why are we holding this exhibition?

To relate a little about the life of someone who, as if prompted by the dictum of Pavese (who also wanted but little of what people could give him) “The only rule of heroism is to be alone, alone, alone”, lived a life alone…

Because of the superhuman effort that he willingly made to contend with life’s difficulties…

Because he created things from a dearth that one scarcely encounters nowadays…

Because he never once strayed from the path he took and followed it to the very end…

Because he was strong enough not to need acceptance or applause…

But most important of all because he had the determination and will to live the things he was passionate about and to live in this society knowing that it would go unrequited…

And ultimately, perhaps because we too long for, yearn for such a life ourselves…

Because we want to be sure that the source of the love for photography that first infected Bilge playing around with that tiny camera Father had brought back from America with so much difficulty and later myself as well and of the progress that both of us made was his own luminous being…

And now that it’s April again and he’s 86 years old, because we sense that the number of days that we have left to spend together with each other is rapidly decreasing…

Before I started writing this piece the other day I called him up on the phone to ask him a few things about his life. “There’s not been anything interesting in my life” he said. “There’s no need for any of this.” “I want to live in my shell” he said. I asked him about his relationship with his own father: “Did he love you?” With some astonishment he replied “There never was anything like that. We just worked.” After a brief pause he said slowly, “I don’t remember anything but working.”

And he added “And that’s how I managed to live as long as I have.”

.......

Many happy returns, Father dearest.

Many happy returns!

|